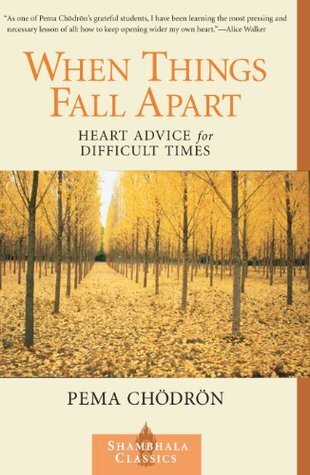

Uncertainty continues to grow and expand and deepen around us, creating perhaps, its own virus, a virus in the heart. We hear the words today, “everything is so fluid and we don’t know what’s next.” My own levels of anxiety continue to rise, so I returned to one of my favorite books by a favorite writer to calm myself: When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times by the Buddhist nun, Pema Chodron. In addition to her gift for bringing some fundamental ideas of Buddhism into the Western world, she was instrumental in founding and directing Gampo Abbey in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, the first Tibetan monastery in North America specifically established for Westerners.

Rereading some select passages lately, I began to notice how her insights on impermanence seemed so applicable to many of our feelings of uncertainty and its first cousin, insecurity, today as the spread of the Corona virus weaves its way into all parts of the planet. I am relearning from Chodron how a pandemic does not have to lead to pandemonium unless we choose it allow it.

She asks us to consider another tact on our feelings of impermanence, going so far as to suggest that “Impermanence is the goodness of reality. . . . Impermanence is the essence of everything” and goes on to observe that “people have no respect for impermanence;. . . in fact, we despair of it. We regard it as pain. We try to resist it by making things that will last—forever.” In doing so, she claims, we can easily “lose our sense of the sacredness of life.”

My sense is that her remarks on impermanence strike close to the heart beat of uncertainty. In fighting either one, I can feel that my reference points in my daily life can be shaken, begin to fall apart and need to be reclaimed not by force but by yielding to and becoming curious about my relation with both impermanence and uncertainty.

I am curious at this stage how any of our reference points of our life can be seen as our reverence points—places in which the sacred-- what we treasure and value--have their most dramatic expressions. What I reference on a daily basis is what I reverence.

Chodron describes at one point how these can become focal points of wisdom, even opportunities to examine life-long habits of responding to them when they appear, which, if not in our current condition of uncertainty of where the virus will take all of us, then when? But her approach goes deeper: she suggests that if we can see ourselves nested within our feelings of impermanence and uncertainty from a place that is not ego-driven, then things transform vividly. Here is what she understands: “Egolessness is available all the time as freshness, openness, delight in our sense perceptions. . . we also experience egolessness when we don’t know what’s happening. . . . We can notice our reactions to that.”

I find her observations worthy of exploration to be curiously comforting as I try to be more relaxed with the uncertainty that faces all of us each day around the planet: will there be enough money, food, health, health-care, cooperation, unity in the face of increasing adversity? When the same old patterns “of grasping and fixating” continue to drive us towards greater insecurity wherein the patterns are repeated with renewed gusto, we can, she notes at the end of her reflections, “relate to our circumstances with bitterness or with openness.”

Our greatest freedom may indeed reside in how we relate to the mess we feel around and perhaps within us.