Published in New Braunfels’ Herald-Zeitung January 2021.

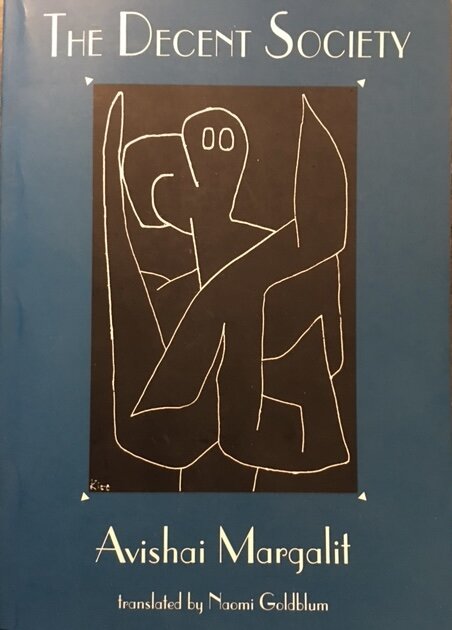

In the wake of the moving and heart-stirring Inauguration were planted the seeds of a new level of integration of our disparate and at time desperate parts of our national soul. It stirred a memory in me, of a book I had begun reading some time ago that inspired me then. I retrieved it from my bookshelf and picked up where I had left off: Rabbi Avishai Margalit’s The Decent Society. The word “decent” has meant, in its origins, “tasteful,” “proper,” “becoming,” “to be fitting or suitable.” Decency claims a right-ful place in any society, especially deeply-afflicted ones.

Margalit reveals that “a decent society is one that does not humiliate or wrest self-control from its weakest members.” To humiliate or demean another, he claims, is “a painful evil.” A decent society “does not injure the civic honor belonging to it.” In such a society, there are no second-class citizens—those who have been shoveled to the margins, whose relative absence of power and position are used against them for personal or corporate gain. How leaders of a people decide to discriminate “in the distribution of goods and services is a form of humiliation.”

We can and have, as a people today, deny selected others “civic privileges,” and by doing so, keep them in place as we have defined their assignment.

What keeps or retards a society from becoming more decent—and perhaps the goal of democracy is less to “form a more perfect union” but to form a more decent union in which all are given opportunities to rise to their most gratifying potentials.

My sense today is that we have at this critical crossroads, this threshold in the political swing of things, a chance to decide whether to stay secure in our silos of sour hearts and prejudiced persuasions, or to engage with all of our talents and innate decencies to enrich the lives and spirits of all of us, for a change, in order to change. Dreams we hold can become nightmares that hold us—back from using the pandemic, economic and psychological crises we are entangled in, to create something new, not desecrate the human possibilities we are.

Allowing ourselves to be inspirited by new attitudes towards our noble natures and at least acknowledge the darkness that resides in each of us, known or not, can lead to leaving our guns at home, both the literal guns we own and the metaphorical guns we aim at others because they differ from us. My poem below is an attempt to express this desire:

Leave Your Gun At Home

Anything will give up its secrets if you love it enough.

—George Washington Carver

If you wish to see the other in

you striding beside your shadow

Leave your gun at home.

If you desire friendship with a stranger

in conversing on topics you share

Leave your gun at home.

If you seek in the folds of a friendship

the virtues of acceptance love and warmth

in the oven of meetings

Leave your gun at home.

If when driving, walking, talking

or teaching

you seek an open response to all

you profess

Leave your gun at home.

For in the pistol’s presence and the

bullets that zing from your mouth

and the full chambers of your heart

and the hammer of a quick response

full of leaden love

and the trigger of a twisted phrase

The other dies in front of you because

in your scattered hail of reports

You brought your gun from home.